-

Title

-

On memory and Its Threats/ Polska Sztuka Ludowa - Konteksty 2014 Special Issue

-

Description

-

Polska Sztuka Ludowa - Konteksty 2014 Special Issue s.21-33

-

Creator

-

Kapuściński, Ryszard

-

Date

-

2014

-

Format

-

application/pdf

-

Identifier

-

oai:cyfrowaetnografia.pl:6074

-

Language

-

ang

-

Publisher

-

Instytut Sztuki PAN

-

Relation

-

oai:cyfrowaetnografia.pl:publication:6502

-

Rights

-

Licencja PIA

-

Subject

-

Kapuściński, Ryszard (1932-207)

-

Type

-

czas.

-

Text

-

Polesia Czar and a childhood

RYSZARD K A P U Ś C I Ń S K I

landscape

Zbigniew Benedyktowicz: W e are to talk about

memory and its significance in contemporaneity as well

as its assorted forms and manners of appearance. Let

us, however, start with your private and most intimate

“memory place”, the very onset of your biography. You

must have been asked often about the Polesie region

and the town of Pińsk - your birthplace and the land

of your childhood...

Ryszard Kapuściński: I am constantly requested to

comment about all sorts of things and endlessly about

Polesie. This is also a moral problem, because I am the

only living writer born in Pińsk. A t the moment, I thus

live as if under social pressure and feel some sort of a

moral obligation. We know very well that everyone is

writing about W ilno and Lwów, and that Polesie and

Pińsk are situated exactly halfway between those two.

Polesie is a somewhat poor and abandoned land and

little has been written about it.

Z. Benedyktowicz: D o you frequently compare

that, which you remember as a child and that, which

you encounter now? Do such confrontations reveal

something permanent?

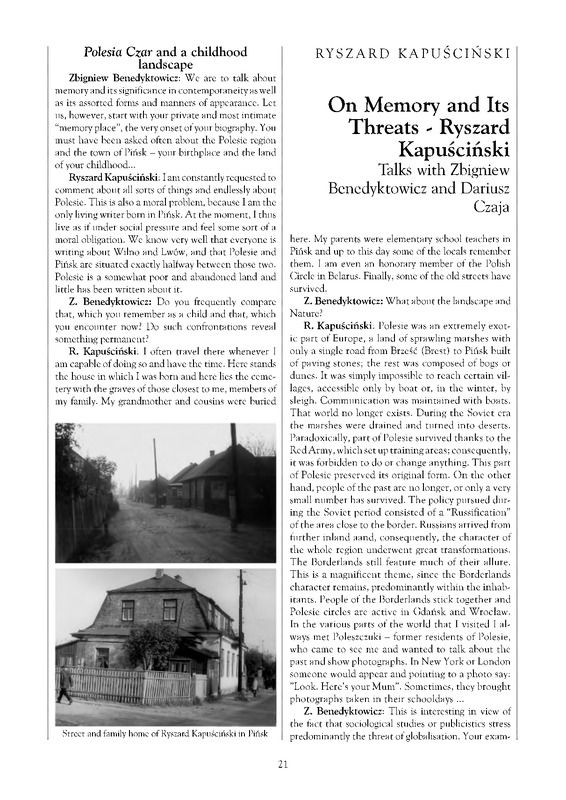

R. Kapuściński: I often travel there whenever I

am capable of doing so and have the time. Here stands

the house in which I was born and here lies the cem e

tery with the graves of those closest to me, members of

my family. My grandmother and cousins were buried

On Memory and Its

Threats - Ryszard

Kapuscinski

Talks with Zbigniew

Benedyktowicz and Dariusz

Czaja

here. My parents were elementary school teachers in

Pińsk and up to this day some of the locals remember

them. I am even an honorary member of the Polish

Circle in Belarus. Finally, some of the old streets have

survived.

Z. Benedyktowicz: W hat about the landscape and

Nature?

R. Kapuściński: Polesie was an extrem ely exo t

ic part of Europe, a land of sprawling m arshes with

only a single road from Brześć (Brest) to Pińsk built

o f paving stones; the rest was com posed of bogs or

dunes. It was simply im possible to reach certain viL

lages, accessible only by boat or, in the winter, by

sleigh. C om m unication was m aintained with boats.

T h at world no longer exists. D uring the Soviet era

the m arshes were drained and turned into deserts.

Paradoxically, part of Polesie survived thanks to the

R ed Army, which set up training areas; consequently,

it was forbidden to do or change anything. This part

o f Polesie preserved its original form. O n the other

hand, people o f the past are no longer, or only a very

small num ber has survived. T he policy pursued dur

ing the Soviet period consisted of a “R ussification ”

o f the area close to the border. R ussians arrived from

further inland aand, consequently, the character of

the whole region underwent great transform ations.

T he Borderlands still feature m uch of their allure.

This is a m agnificent them e, since the Borderlands

ch aracter rem ains, predom inantly within the in h ab

itants. People of the Borderlands stick together and

Polesie circles are active in G dań sk and W roclaw .

In the various parts o f the world that I visited I al

ways m et Poleszczuki - former residents o f Polesie,

who came to see me and w anted to talk about the

past and show photographs. In N ew York or London

som eone w ould appear and pointing to a photo say:

’’Look. H ere’s your M um ” . Som etim es, they brought

photographs taken in their schooldays ...

Z. Benedyktowicz: This is interesting in view of

the fact that sociological studies or publicistics stress

predominantly the threat of globalisation. Your exam-

Street and family home of Ryszard Kapuściński in Pińsk

21

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

shall be leaving soon?” A n d that person sits down and

describes everything. The recollections are at times

extraordinary, as in the case of a 90 years-old lady who

now lives near W roclaw. I also possess an enormous

collection of photographs. It was even suggested to

organise a large-scale exhibition of my photographs

of Pińsk. This memory about a world of the past is

really very much alive. Travelling across the world I

appreciate the power of the feeling of identity and at

tachm ent to one’s birthplace, that small homeland.

Despite enormous and growing emigration people

leaving their native land take those feelings with them

and thus cherish the strongest possible connection

with the “small hom eland” . This awareness of identity

linked with a concrete place is m an’s great need. It is

the reason why A frica is so fascinating as a continent

that has preserved tribal awareness in a most visible,

palpable, and experienced form. This is not the con

sciousness of a “generalised” person, but regional, lo

cal awareness. Apparently, there is no such thing as an

awareness of the hom eland - the homeland is a fluid

concept in the history of societies, a rather artificial

product of our mentality; it is tribal awareness that is

the strongest in man.

Z. Benedyktowicz: W hat if we were to try to es

tablish at this exact moment that what has been pre

served in your memory first and foremost?

R. Kapuściński: W hat do I remember? It seems to

me that we are dealing here with a much wider prob

lem. My thesis about memory is as follows - ask: when

does man come into being? N ot biologically, but when

does he start existing as a human being? In my opinion,

he emerges with the very first reminiscence that can

be reached. W e thus search while saying: “I remember

this, and this, and one more thing”, and in this way we

arrive at the very first recollection when we no longer

remember anything that occurred earlier. It is exactly

at that point that m an begins and ”1” emerges, that my

identity and my extremely individual, private life story

start. I am in the habit of asking people: “W hat is the

first recollection of your life?” Two things arise upon

this occasion.

T he first is the discovery that so few people actu

ally think about this, and that they begin to labo

riously recollect. Generally speaking, people do not

ponder this theme and are forced to dig deep in order

to reach their first memory. The second issue con

cerns the character of those reminiscences. I have

asked hundreds of people about this, and it is inter

esting to discover that each has different recollec

tions. Som e are linked with a cat, another - with a

fire, and yet others with a boiled sweet purchased

by grandm other. These rem iniscences vary greatly,

and are one of the proofs of m an’s differentiation.

A lready the very first recollections distinguish us to

such a great extent.

In Polesie...

In New York... New York 1984- Photo: Andrzej Strumiłło

ple shows how assorted local peripheral cultures suc

cessfully function alongside this p ro c e ss...

R. Kapuściński: Yes, this is an extremely strong phe

nomenon. I believe that it is the reverse of globalisation.

It is the latter menace that sets free a feeling of distinct

ness, a certain need for identity and belonging to some

sort of a local community. Those bonds are extremely

powerful. It is because I come from Pińsk that people

bring to those meetings assorted photographs and items

that they took from there. These durable relations con

tain a certain emotional load. The people in question

are extremely proud of the fact that they are the carriers

of memory and willingly gather to reminisce.

By way of example, I say: “Alright, would you like

to write all this down and then mail it to me, because I

22

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

Dariusz Czaja: What do you consider to be the

point of departure for memory? W hat is it? Is it a

word? Colour ...?

R. Kapuściński: An image!

Z. Benedyktowicz: An image? And not sound?

R. Kapuściński: It will always be an image. After

all, we know that earliest reminiscences concern the

period when we were three or four years old, more or

less the age when a child thinks in images. As a rule,

this is a case of visual recollections. Even if there did

take place some sort of a loud noise, such as thunder,

it too must have been associated with an image, either

of a storm or the place where it took place. I always

found this phenomenon extremely interesting and

noteworthy. I would like to write about my childhood

in Pińsk.

the operation of introducing order and hierarchy, the

arrangement of memory, becomes extremely relevant.

I think in a certain way because I am writing an auto

biographical reportage and constantly encounter this

problem. I recall an episode from an African country

but cannot remember when it took place. What oc

curred “before” and “after”? Did I stay there in 1967 or

perhaps in 1968? Was it Ghana or rather the Republic

of South Africa? Here problems start and demand se

rious effort.

Z. Benedyktowicz: Do you keep such a diary?

R. Kapuściński: No, I am incapable of doing this

simply because my journeys are extremely exhausting

physically. A s a rule, they take place in the tropics,

there is a lot of work in progress and texts that have

to be immediately handed over; later, I am so tired

that I do not have the strength for anything else. Years

later, I am compelled to reconstruct the past out of

elements: airplane tickets, passport visas, various o

ther things. Furthermore, there is yet another

problem, the reason why I am not a great enthusiast of

diaries. A person who keeps a diary writes down every

day that, which he regards as important. Reading it

years later it turns out that usually such records make

but a slight contribution. This fact is associated with

the selective role of memory.

Take the highly instructive reminiscence about

Gorky, who upon a certain occasion was introduced

to a young writer named Paustovsky who brought one

of his stories. Gorky read it and they made an arrange

ment to meet again. Gorky said: "Young man, this text

shows talent, but I would like to give you a piece of ad

vice: spend the next ten years travelling across Russia,

working and earning a living. Write nothing. Do not

keep any notes. Once you return, make a record of all

that you saw. Why then? Because you shall remember

that, which was truly significant, while that, which you

do not recall was simply not worth remembering”.

A t this moment I am writing Podróże z Herodotem,

i.e. about experiences that took place in the 1950s. I

still recall them. By way of example, in 1956, upon the

wave of the October thaw, my editorial board sent me

for the first time to India. I flew via Rome, in an old

wartime DC-3. The airplane landed in Rome in the

evening. For the first time in my life I saw a town all

lit up. This came as such a shock that although fifty

years have passed I still remember precisely the view

of the illuminated city at night.... This is why I firmly

believe in the selective role played by memory. There

is no need to member everything because such a proc

ess serves no purpose.

D. Czaja: But this would produce an interesting

conclusion. Apparently, it is not we who consciously

and intentionally put those data into order or con

struct an image of the past pertaining to us; this proc

ess takes place somewhere “in the back of the head”,

The chaos of memory and the order

introduced into it

Z. Benedyktowicz: You have just mentioned that,

as a rule, people are forced to delve deep into their

memory in order to reach their first reminiscence. Did

you encounter such a phenomenon also in your life,

when earliest recollections find themselves beneath

those that are “worked over”, and about which we

know that they are the property of others and had

been already heard somewhere?

R. Kapuściński: Yes, this has to be cleared up.

This is the Husserlian idea of purification. Arrival at

these primary things is extremely difficult, especially

in the case of those about which we had been already

told. This is connected with two overlapping problems

with memory and reminiscences. The first is the in

troduction of order. It turns out that we find it very

difficult to put all those recalled images into order

and thus encounter certain chaos. In other words, the

process of introducing order must be purposeful, con

scious, and intended - I must arrange everything in or

der and determine what was “before” or “after”. It be

comes necessary to establish the sequences of certain

events. This is extremely important for memory. Sec

ondly, that, which is essentially linked with memory

or perhaps with its absence is the fact that memory is

fragmentary and without a continuum. We remember

only certain episodes from the past but do not have

access to their complete sequence.

D. Czaja: Additionally, it is interesting to note

that we immediately arrange them into some sort of a

plot, construe narration, and gather those details into

a linear sequence.

R. Kapuściński: We have to do this, otherwise

we shall get lost and everything will simply scatter. In

other words, in order for memory to function usefully

it requires certain operations and effort. This is not

automatic since that, which autonomously imposes

itself is chaotic, fragmentary, and non-cohesive. Only

23

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

without our will. In other words, we contain some sort

of a selection mechanism that is nothing else but a

resultant of all the significant events in our heretofore

life.

R. Kapuściński: Yes. It is not that, which I daily

decide that I shall remember or forget that is impor

tant. It suddenly turns out that I recall a certain thing,

which, actually, I should not remember but by some

miracle it exists in my memory. Then I start wonder

ing why this is taking place and why I recollect pre

cisely that thing and not another.

D. Czaja: A t this stage there comes into being a

certain subtlety, not to say: difficulty, probably not the

last that we shall discuss today while drifting between

memory and oblivion. I have in mind selection associ

ated with memory. You mentioned the “introduction

of order” into memory data. If we, however, perform

a slight semantic retouching then we shall immedi

ately arrive at the “construction” of memory. Another

slight shift and we are dealing with a “mythicisation”

of memory. How can those subtleties be separated? Is

it at all possible to introduce some sort of an acute

distinction? When do we once again deal with such

remembrance of the past about which we may say:

"This truly took place”, and when with something that

I described as the mythologisation of memory or, if we

speak about the collective dimension, with the ideologisation of memory? After all, each of those operations

performs some sort of a selection, right?

R. Kapuściński: In my opinion there is no unam

biguous response to this question. All depends on the

given person, the situation in which he finds himself,

and many different factors. As a reporter I might say

that in this case the foundation is some sort of an ethi

cal attitude, an elementary compulsion that says: “I

remember that”. This means that I am responsible for

what I wrote. In other words, I guarantee that I had

really experienced something, that the book contains

my experience. This was my argument while writing at

the time of prevailing censorship. If the censors com

plained I answered: ”I was there, and if you want to,

then come with me”. It seems to me that personal expe

rience constituted the foundation of what I wrote. A t

the same time, it provided me with a feeling of power.

I do not know how to write, nor am I a typical author.

My problem consists of the fact that I am deprived of

that sort of imagination, and thus I have to actually be

everywhere in order to write something, I have to per

sonally remember things. Everything must leave a di

rect imprint on my memory. Then, when I come back,

I do not deliberate about the form in which I am going

to write - a poem, a drama or a philosophical treatise;

I simply try to write a text. The point is for this text

to be the most faithful recreation of the memory of my

experiences, of what I saw and thought. Naturally, I

am fully aware that this is all very subjective, i.e. that

everyone sees reality differently. I often encountered

this phenomenon during assorted meetings with my

readers. Someone stands up and says: "Mister, I saw

what you described but it was quite different...”. And

I absolutely believe him because the number of as

sorted versions of the same events corresponds to the

number of its witnesses. Consequently, there is no such

thing as objective memory. Nothing of the sort exists.

Memory is the most subjectivised element of culture.

We really remember extremely different things. I have

a sister who is a year younger and lives in Canada. I

did not see her for years and once we met I, thinking

about Pińsk, reached for a tape recorder, saying: "Ba

sia, what do you recollect from our years in Pińsk?”.

Let me add that we are very close and when we were

little we always walked holding hands. One could thus

say that we saw exactly the same thing. When she be

gan to extract reflections from her memory it turned

out that they were totally different from mine. In other

words: she remembered things that I did not recollect

at all. And vice versa. You can see just how strong is

the individualisation of memory. As a result, I always

use the formula: “according to me, this is what hap

pened”. I could never say that my perception is the

only true one.

Z. Benedyktowicz: Despite this radical subjectivisation of memory there also exists something like

the memory of a generation, perhaps not as objective

but one in which people can at least recognise them

selves...

R. Kapuściński: Naturally. The memory of a gen

eration or of a nation - they both exist. Just like col

lective memory I too possess deep archetypical strata,

that whole Jungian phenomenon. But in my personal

experience as a reporter, a person travelling around

the world, collecting observations and stories, and

writing about them I am most fascinated by the fact

that memory is individualised...

D. Czaja: ... that the past is perceived differently in

each personal experience ...

R. Kapuściński: ... extremely so. This is what I

find so fascinating in Herodotus, because it turns out

that he already tackled these difficulties. The reason

lay in the fact that his writing was connected directly

with the problem of memory. Recall the opening invo

cation of his book: These are the researches of Herodotus

of Halicarnassus, which he publishes in the hope of there

by preserving from decay the remembrance of what men

have done. Herodotus struggled with the obliteration

of memory, encountered already at the time. By way

of example, upon his arrival in Thebes he discovered

that everyone said something different about a certain

past event. To this he responded that he was obliged

to describe assorted versions. His task consisted of a

faithful presentation. He felt compelled to propose

an objective account. It was Herodotus who was the

24

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

first in world literature to announce this differentia

tion of memory and the image of the past. We know,

however, that past reality resembles quicksand. We all

make our way along this sandy terrain, of which no

one is certain.

D. Czaja: There undoubtedly exists some sort of

tension between subjectivity and the objective image

of a thing. You mentioned that Herodotus attempted

to coordinate various versions of the past. He too,

however, was probably not free from subjectivity.

Within the context of your recollections of the past

you mention the individualisation of memory and the

subjectivity of the image of the past. There arises the

following problem: what is the situation of an historian

who tries to trust memory (witnesses or documents)

but, at the same time, tries to solve the question re

peated after Ranke: “What actually happened” (wie es

eigentlich gewesen)? To put it directly: he attempts to

be objective. Do you, in the wake of numerous texts

demythologising our naive faith in “genuine reality”

recreated by the historian, still believe in the objectiv

ism of historical studies, the scientific, to coin a term,

image of the past?

R. Kapuściński: My approach is as follows: I re

gard the key to such situations and problems to be

the French term: approximation. In other words, such

objectivism is possible only in an approximated form.

Approximation means that we harbour certain ideals,

which we accept and in some way assume. I would like

to write an ideal book. But all that I am capable of do

ing is, at best, to come close to the theoretical ideal,

which I have adopted. The same situation occurs in

science and the humanities. Everything is approximation. Importance is attached to the degree in which we

manage to approximate this devised collective ideal.

Some succeed in approaching it extremely close whilst

others will never attain it. An historian who assumes

that he will write an objective book about the battle

of Grunwald also presupposes some sort of cognitive

ideal. The degree to which he will attain it will be

come the yardstick of his work. We cannot achieve

an absolute because this is simply impossible, and the

yardstick of assessing our effort is the degree of ap

proximation to this absolute.

D. Czaja: Fine, but how do we know that we are

coming close to the epistemological absolute?

R. Kapuściński: Social awareness contains a func

tioning concept of the ideal. We feel that a certain

novel, for example, In Search of Lost Time by Proust,

comes close to it, or that Joyce succeeded, but some

inferior author did not. This is a collective comprehen

sion of the ideal, just as Znaniecki wrote in Społeczne

role uczonych that someone is eminent in a given do

main of science. How is one to define who is brilliant

in a certain field? The solution proposed by znaniecki

claims that a group of specialists regards someone as

outstanding. This is the criterion, and there is no oth

er. In my opinion, the same holds true for every ideal.

D. Czaja: In other words, this would take place

according to the principle of some sort of consensus, a

collective contract, right?

R. Kapuściński: Yes, this is the case. Joint reflec

tion, joint evaluation, joint comprehension. This is

how I envisage it. I am incapable of discovering a dif

ferent criterion defining why a particular reportage is

considered better than another. People, members of a

group, simply think that someone is better, another is

worse, and yet another is superior.

D. Czaja: Or could it be that what we describe

as “the truth of the past” is simply a function of the

time, in which it had been formulated? Let us take a

closer look at mediaevalist research in the past several

decades. After all, this is not the case of an avalanche

discovery of some new, previously unknown docu

ments. The image of the Middle Ages, nonetheless,

changed from the infamous “Dark Ages” to excellent

multi-strata studies, such as those by Gurievich or re

cent publications by Le Roy Ladurie. What will hap

pen to those visions of the Middle Ages in another

several decades?

R. Kapuściński: The humanities as a whole are

deeply immersed in living and endlessly active matter.

In Brzozowski’s brilliant definition of memory the lat

ter is always working and transposing, and there is no

such thing about which we could find out something

once and for all. He was of the opinion that it is matter

that succumbs to constant transformation.

D. Czaja: If this is so, then perhaps it is the ideal as

such that is fiction?

R. Kapuściński: Yes, because this ideal too chang

es. I maintain that the greatness of the humanities

consists of the fact that we permanently work with

matter subjected to limitless transformation. It is fasci

nating to follow its trends and assorted varieties. This

is what I find so unusual and interesting. Furthermore,

it testifies to the quality of the human intellect.

B ad memory, repressed memory

D. Czaja: We are speaking the whole time about

the positive function of memory, memory that sal

vages, creative memory, and, finally, memory build

ing our identity thanks to which we know who we are

and where we come from. I would like us - and by no

means due to contrariness - to speak for a while about

the sort of memory that can produce resistance and

about unwanted, negative memory.

Our discussion thus cannot lack Nietzsche and his

celebrated and highly controversial text : On the Use

and Abuse of History for Life. What does Nietzsche tell

us? He declared more or less: why do you want to re

member? This is the hump that you carry at all times.

The excess of history has seized the plastic force of life. It

25

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

no longer understands how to make use of the past as a

powerful nourishment. A whole diatribe against histo

rians and the historical sense. Nietzsche criticised a

stand that perceives the world through the prism of

sight always focused on the past. He was irritated by

the fact that in this manner we build a society that

erects shrines to the past and the old.

My question too embarks upon this Nietzschean

motif of memory that could become a burden and an

obstacle, and which does not create but hampers, es

pecially if it pertains to a cohesive tribal group. Take

the example of the war in the Balkans. It is said at

times, while observing the frenzied Balkan melting

pot, that, paradoxically, if local population groups re

membered less and did not accuse each other of the

suffering endured in the past, during the lifetime of

their fathers or grandparents, and if they were capable

of forgetting, then the bloody massacres of the 1990s

would have never taken place. What is your opinion

about such a portrayal of this issue?

R. Kapuściński: I do not share this opinion. I

disagree with Nietzsche, especially considering that

today we endure assorted problems involving memory

and there exist a number of serious threats entailing

memory loss.

On the other hand, here are several remarks about

tribalism. Unfortunately, this particular word is en

dowed with a negative meaning and Africans find

its use offensive and prefer “nationality” or “people”.

They consider tribe or tribalism to be anathema.

In order to understand what actually took place in

the Balkans it is necessary to introduce a certain dif

ferentiation, to distinguish between tribal awareness

and its use for political purposes and strife. This some

what resembles the use of a knife to cut bread and ...

throats. The same holds true for tribalism, which in

itself is an enormous value to be applied either for the

sake of a political game or one conducted for winning

power and certain political profits. From this point of

view, tribalism is a powerful feeling of local commu

nity, neither better nor worse than any other emotion.

In political games it is possible to make use of every

sort of feeling with a tangible outcome. In the Balkans

such emotions were applied for destructive and out

right murderous purposes. After all, scores of genera

tions led normal lives in harmony. Mixed marriages

abounded. Pińsk, where I was born, was an interna

tional small town, where 72% of the population was

composed of Jews, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Latvians

and Lithuanians. There was no feeling of radical ani

mosity. Leaving Pińsk I was bereft of all ethnic aware

ness and was even unconscious of its existence. We all

lived together. As long as a burning fuse is not inserted

into such diverse matter - and this can be done only

from the outside - there is no threat. It is not part of

man’s nature, and without that external factor he will

not become ablaze with hatred. This is simply some

thing that man lacks.

D. Czaja: I seriously doubt it. After all, we all be

long to “the tribe of Cain”, right? I recently watched a

shocking British documentary about Srebrenica. N at

urally, we know that men have been killing as long

as the world exists, but the scale and type of those

murders, totally impartial, exceeds all boundaries of

our imagination...

R. Kapuściński: True, this is already bestiality.

Once the wheel of hatred is set into motion it be

comes difficult to stop it. I constantly repeat that I am

concerned with one thing: that people will never start

anything of this sort by themselves! Take the example

of a multi-tribal African town in which every inhab

itant has his street and house. Nothing special takes

place. Suddenly, one day, agitators arrive and declare:

“Listen, you’re poor while that man on the next street

is a member of the ruling elite; wouldn’t you like to

be one, too? If you continue to remain passive you’ll

die of hunger and achieve nothing...”. This is the way

things start. People go into the streets brandishing

machetes and start fighting “for their cause”, killing

and assaulting. This is the type of mechanism I am

concerned with. More exactly, I am anxious about the

fact that such a feeling of tribal affiliation may be eas

ily used for political purposes.

D. Czaja: I agree, but it must fall on susceptible

ground. Inciting one against the other only awakens

dormant demons. And they do really exist!

R. Kapuściński: True, very often they only have

to be awakened. I do not maintain that man is an ideal

creature, but I do claim that every person contains all

sorts of features. It all depends on the sort of traits to

which we refer and which we stir. I affirm that man

as such does not act in this manner as if “from the in

side” and that only certain circumstances will awaken

the negative, dark side. This is what I have in mind.

True, such darkness exists as an imminent component

in a dormant state that could be described as passive.

In order to achieve it, it is necessary to create suit

able conditions. This is the case with tribalism. On the

other hand, I repeat obstinately that clan, family or

tribal bonds are an extremely positive emotion since

it enables us to function in the world. An individual

simply cannot exist outside a clan. This is the essence

of the philosophy of African societies and, generally

speaking, the philosophy of clan societies as such.

Here lies also one of the differences between the

East and the West. In Western civilisation it is the in

dividual who is the most prominent, and we deal with

the liberty of the individual, his rights, and so on. In

non-Western societies the situation is the reverse supreme value is attached to the collective, a fact that

simply follows from different historical experience, i.e.

the individual could not survive in conditions created

26

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

by local poverty and is forced to seek the support of

the community. Only the latter is capable of facing

Nature. The individual is incapable of doing this and

of taming Nature. In a word, subjugation to the col

lective is a condition for endurance in contrast to

developed Western civilisation where the individual

can easily survive and relish assorted rights. This is a

certain luxury, i.e. the enjoyment of civic rights and

similar privileges that the highly technological society

can well afford. Poor society, dependent on Nature,

cannot afford this.

Back to the Balkans. The whole story, as we know,

started at the time of the Turkish invasion. Previously,

this was a normal and peaceful community. A t a cer

tain moment, tribal animosities were stimulated and

kept alive. A t this stage, the basic issue comes to the

fore. My theory about the origin of tribal and national

conflicts claims that war did not start on 1 Septem

ber 1939, nor did it break out on the day when the

first shots were fired. In the contemporary world, war

begins with changes in the language of propaganda.

Whenever we observe language and the way in which

it transforms itself and certain words start to appear

then it becomes obvious that suddenly there come

into being such terms as: enemy, foe, to destroy, to

kill ... i.e. there emerges a language of aggression and

hatred or, to put it differently, so-called hate speech.

There is still no sign of war and nothing is said about

it, but the language of communication begins to alter.

A t that very moment, in the wake of those vagaries of

the language and their intensification, we notice the

looming menace of war. This process could be classi

cally observed in the Balkans. I claim that each war,

be it in Iraq, the Balkans or any other country, starts

in this manner.

D. Czaja: Let us, therefore, make matters clear.

Our issue presents an extremely interesting fragment

of the most recent book by Paul Ricoeur on history,

memory, and oblivion. We include a chapter on how

to successfully tackle the difficult problem of bad

memory. This is a thoroughly practical question and

I am even inclined to agree with you that tribalism as

such is not a threat. The war in the Balkans has come

to an end, and now what? What about memory that

does not wish to forget? What should be done about

it? It is easy to say: testify, educate, and teach. All this

is fine, but we do not really believe in the effective

ness of such activity. After all, we had our Sqsiedzi.

We also recently held a difficult and painful discus

sion about Jedwabne. Now what? Should the whole

problem be simply described, explained, recalled, and

taught at school? Certainly. But something else must

also be done. I agree with Ricoeur who wrote about

the need for the Freudian term: “the work of mourn

ing” , some sort of grief tackling the past. Powerful suf

fering, a process of filtering the facts. Otherwise, when

traumatic experiences of the past become relegated to

textbooks or even, as in the case of Jedwabne, state

ceremonies are held, without private mourning we

shall as a community enjoy the comfort of feeling that

everything has been already done and now we can en

joy peace and quiet. It has all become part of the past.

What is your opinion?

R. Kapuściński: Naturally, this is an extensive

theme, dramatic and, for all practical purposes, one

that does not offer any solutions. I have in mind the

fact that the moment when such development has

been revealed, the dynamic of destructive processes

is appalling. Once this Pandora’s box has been opened

it becomes extremely difficult to close it again. It will

probably be never possible to shut it tightly, a feat that

will remain unaccomplished for the next few genera

tions. It is here that time starts to exert an impact.

The once incited bloody conflict and the instigation of

hatred possess terrible results and cannot be set right

in a brief space of time. This is an exceedingly pain

ful circumstance. Man’s great frailty consists of the

fact that he is unable to abandon it either ultimately

or satisfactorily for many generations. Up to this very

day, despite the passage of decades, certain societies

are completely unable to confront reality. By way of

example, Japanese society still refuses to settle ac

counts with the memory of its past crimes. This great

nation is incapable of even approaching the problem.

I believe that the task in question is too demanding

and horrible ...

D. Czaja: But something must be done and things

cannot be left unchanged.

R. Kapuściński: Theoretically, you are right.

Naturally, I have in mind good will and intentions. In

such cases it is necessary to return to those problems,

face them, and mull them over. Once again, this has

to be attained with a conviction that in this case too

there functions an approximation mechanism, i.e. that

we may only draw closer to the solution of such ques

tions. This is a case of human weakness, and matters

of this sort cannot be ultimately resolved.

D. Czaja: Perhaps this could become the moment

when it becomes possible to embark upon the work of,

so to speak, wise forgetting. The latter would involve

grief or at the very least be preceded by some sort of

reflection, if not atonement.

R. Kapuściński: Yes, this is certainly right. None

theless, the process in question could be accomplished

in relation to only a certain part of society or individu

als, but it is difficult to imagine that it could refer to

entire societies and communities.

D. Czaja: I insist that something should be done

because scores of examples testify that a simple ejec

tion of traumatic past events from memory actually

does not yield anything.

27

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

R. Kapuściński: It generates nothing because real

an avalanche, a burden that makes life impossible and

produces permanent exhaustion. Existing information

exceeds many times the capacity of the average hu

man intellect.

Finally, the third threat involves the enormous

acceleration of historical processes. This means that

history used to follow a slow course. Three hundred

years ago nothing took place, two hundred years ago

- the same, and the human mind was adapted to that

tempo. Man could absorb historical moments and

those of his life. History exerted a stabilising effect.

Man lived in a constant environment, which he was

capable of encompassing within his memory and mas

tering. Now, due to terrible acceleration, on the one

hand, temporal and, on the other hand, spatial, with

space and time acting as our two fundamental orien

tation points in the world we have lost the feeling of

stabilisation and enrootment in the world.

D. Czaja: How would you, in connection with this

multi-trend loss of memory by contemporary society,

define our epoch, the time in which we live? By way

of example, Pierre Nora, author of the already classi

cal Les Lieux de mémoire, seems to be saying something

quite different: we live at a time of commemoration, a

time of gathering memories. Take a look at numerous

memory “sites”: museums, archives, compendia, dia

ries, monuments - assorted “appliances” for remem

bering. What is actually taking place: are we living at

a time of memory or a time of forgetting?

R. Kapuściński: Naturally, museums and archives

do exist. I, however, am concerned with something

quite different, namely, that more and more of our

interior is being extracted and delegated to assorted

institutions. I have in mind the entire institutionalisa

tion and bureaucratisation of memory. Various insti

tutions are being established - in Poland, for example,

the Institute of National Remembrance - to organise

our memory. We are becoming increasingly convinced

that “they” will deal with the issue at stake. “They”

have their archives and the individual, as I have men

tioned, is getting rid of his memory and dispatching it

to an anonymous institution. I am concerned with dis

tinctive memory, the sort that differentiates us. This

is the memory that we develop in time and via which

we create ourselves, our identity, and personality. We

differ, i.a. due to the fact that we have diverse memo

ries, that each one of us remembers different things

and values, and becomes attached to certain stages or

types of memory.

Furthermore, I am concerned with the fact that

the statement that we live at a time of remembrance

can be at most a symbol of the fact that we live at a

time of increasingly institutionalised memory and less

so at a time of memory as a personal, private value.

D. Czaja: Perhaps it would be possible to com

bine those two things. It could be deduced already

ity stays on.

D. Czaja: Sometimes, it returns with even greater

force.

R. Kapuściński: Yes. I think that this is one of

those weaknesses of human nature, the nature of

societies with which we simply do not know how to

deal. There are multiple things about which we do not

know what should be done. They entail great themes

and equally great weaknesses, such as human cruel

ty. For centuries, people have been embarking upon

similar questions and we are still incapable of tackling

them successfully. Dostoevsky was always fascinated

by the mystery of unnecessary, disinterested cruelty. A

person has killed? Yes. But why does he quarter, slice,

boil, why does he additionally... why, why...?

We are incapable of resolving such questions. The

essence and greatness of the humanities probably lie in

the fact that they recognize the existence of a range of

queries to which we shall never find solutions.

Threats to memory and time of

commemoration

Z. Benedyktowicz: Let us now discuss the threats

to memory looming in contemporary culture, which

you mentioned on the margin. In what domains of life

would you situate them? O f what are they supposed

to consist?

R. Kapuściński: In my opinion, there are three

such threats. The first entails the enormous develop

ment of mechanical memory carriers, which means

that man is slowly unlearning the art of remembrance.

The art of memory is something that has to be mas

tered; one has to learn how to remember. Today,

everything is transposed into a computer, a book, a

record, an encyclopaedia. We no longer- as has been

the case until recently - have to learn everything by

heart nor do we have to train our memory since eve

rything is recorded on assorted carriers. Memory is as

if relegated from our heads and transferred into me

chanical memory carriers although it is an absolutely

essential part of human awareness, which Plato de

scribed as the soul. The process of getting rid of the art

of remembrance poses a very grave menace for human

personality. This is by no means a purely mechanical

problem. It is something more: it pertains to man’s

skills and ability to think, to his and our identity. This

peril is growing. In the course of the development of

the “net” and the computerisation and electronisation

of life we shall steadily become invalids as far as our

memory is concerned.

The second threat facing memory is, in my opin

ion, an excess of data. As the British say: abundance

of riches. Human awareness is simply flooded with

such an amount of information that it is no longer ca

pable of mastering it. This excess acts in the manner of

28

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

Africa. Photo: Ryszard Kapuściński

29

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

from what you have said that the search conducted in

one’s past, described by scholars, the quest for family

genealogies, literary or cinematic returns to the time

of childhood, museum tours, the universal predilec

tion among readers for diaries, and various types of

nostalgia, in a word, the whole movement “towards

memory” is some sort of a counter-reaction to the

earlier mentioned civilisation acceleration. Could this

be an instinctive defence against Milosz’s accélération

d’histoire, that powerful and still encroaching variabil

ity of daily life?

R. Kapuściński: I do not claim that these phenom

ena exclude each other. I do maintain, however, that

the situation in which the art of remembering is hand

ed over to institutions is a dangerous tendency. Nor

do I insist that this is a case of either one or the other.

We know that by the very nature of things man is a

lazy creature and prefers to seek diverse facilitations

in life; hence I discern in this process a trend towards

rendering life easier. This is not a charge addressed

against technology. Imagine, however, a situation in

which everything has been already computerised and

suddenly a virus attacks this digitally recorded mem

ory. It could then turn out that we shall remain to

tally deprived of all memory. Naturally, I am speaking

about certain hazards, those bad paths of civilizational

progress. I do not maintain that all is a catastrophe nor

do I prophecy the end of the world.

Z. Benedyktowicz: Earlier, you mentioned threats

facing memory in the contemporary world in connec

tion with the development of new technologies. To

what extent, in your opinion, could conventional di

visions into societies “with history” and “without his

tory”, once existing in anthropology, be referred to

the contemporary world? Is it possible to speak today

about “societies with memory” and “without memo

ry”? Characteristically, American culture used to be

described as culture without memory not because it

has a relatively brief history but also owing to a dis

tinct appreciation of the present, for living for the mo

ment, for life without that constant gazing into the

past, so typical for Europe. Quite possibly, the absence

of significant traumatic experiences is the reason why

in that model of culture people are so insensitive to

the past and do not experience so strongly the pres

sure of the duty to remember and to conserve memo

ry. Is American culture really like that? How does this

appear from the perspective of your American experi

ences?

R. Kapuściński: We live in a world in which mul

ticultural qualities are a norm. We are enclosed within

a world of assorted cultures and traditions offering us

totally dissimilar commodities. On the one hand, we

are dealing with societies dominated by oral cultures:

i.e. the societies of America, Latin America or Asia,

where this symptom of values really prevails. There

exists yet another type of society, bearing the heavy

burden of historical thought. It includes our society

and European societies in general. History constitutes

a large part of our culture: historical thought, the sym

bolic of historical memory, the feeling of a continuum

in time. Then there is a third group of new societies,

whose roots stem from emigration and whose history is

relatively brief: the USA, Canada, Australia, and oth

er, smaller ones. They are no more than 200 years old

and are not burdened with history; thus their world

faces the future. One could say that the future is their

past.

But this too is changing. Take a look at all that,

which transpired in the US in the wake of 11 Septem

ber. This was a classical example of building own tradi

tion, a nobilitation of patriotism, and the construction

of identity around such symbolic signs as the flag and

the anthem. These new societies clearly experience

the need to create national identity, which they can

not derive from the past since they simply do not have

it. They lack some sort of a “battle of Grunwald” or an

event with a similar rank. Hence, they are compelled

to erect this “past” ad hoc. I would not be inclined to

say that this is a bad thing. Generally speaking, they

find the idea of hierarchising culture strange. Such a

society is what it is because it has a certain history and

simply has to be accepted as such.

D. Czaja: Nonetheless, it is possible to observe in

American culture also other types of a return to the past,

this time in a rather more grotesque version. Take the

example of the rather comical snobbery for “the old”,

naturally in its European version. “American” books

by Eco or Baudrillard mention all those churches or

castles transferred to distant Idaho and there recreated

anew brick by brick, as well as other artificial practices

of prolonging one’s lineage. Naturally, this is not only

an American speciality. What are we to think, for in

stance, about the contemporary phenomenon - actu

ally, a fashion - for an artificial resurrection of the past,

a costume-like enlivening of memory? You mentioned

a moment ago the battle of Grunwald, which reminds

me of a certain amusing newspaper article about the

annual recreation of the “battle of Grunwald” on the

historical site, involving teams of knights, “our” men

and the enemy, using swords and lances and engaged

in armed skirmishes. Interestingly, the outcome is not

historically predetermined. I even recently heard that

the Teutonic Knights won [laughter]. How would you

assess those returns to the past, the whole process of

putting on - literally and metaphorically - someone

else’s costume? Just how sensible is this theatralisation

of memory, which some might find funny and others

- grotesque? Do such journeys into the past actually

assist in regaining memory?

R. Kapuściński: I would say that as long as people

are not killing or setting fire to each other...

30

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

Africa. Photo: Ryszard Kapuściński

31

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

D. Czaja: ... then let them play...

R. Kapuściński: Yes, let them play. I, theretofore,

hanged...” sort. Everything is forgotten. Something quite

different is at stake, and this is a model of culture totally

different from its European counterpart. Start with the

fact that the dead must be immediately buried. The first

reaction is to instantly inter the person who died or had

been killed. There is no funeral ceremony or prepara

tions of the sort known to us...

This fact is also connected with a totally different

attitude to time, its treatment and experiencing. If an

ancestor is recalled then not as a martyr but because

he is still alive, participates in the life of the community

by giving advice, metes punishment or reprimands; in a

word, he remains next to, and together with us. Signifi

cantly, such ancestors are buried in the direct proximity

of the homestead. Numerous graves are located next to

homes and often the living walk over them. The ances

tor seems to have departed but he remains an extremely

ambivalent figure. It is impossible to totally forget him

because he continues to function. Illness among the liv

ing could be a sign that we have neglected some of our

duties vis a vis the ancestor, who in this way reminds us

that he still exists.

Z. Benedyktowicz: Perhaps this awareness that

ancestors continue to accompany us does not generate

martyrological remembrance and cultural martyrdom?

R. Kapuściński: Yes, because belief in the presence

of the deceased is extremely strong. This holds true not

only for African religions. Such a conviction about the

return of the dead is a constant component of numerous

religions in which the boundary between life and death

is never final or total. Such an approach remains so abso

lutely at odds with our culture in which death is a terrible

caesura. There it is fluent reality. Consequently, despair

is also dissimilar and extremely theatrical, since basically

death is something quite natural. I always experienced

this as a problem on assorted African frontlines. Some

times, accompanying these men I realised that they were

facing certain death. They, on the other hand, treated

it as something normal; quite simply: someone dies. The

relation between the living and the dead differs. This is a

positive philosophy inasmuch as death does not produce

such a terrible gap in the world around us. It is not hor

rendous tragedy or insufferable pain.

Remember that the average African woman used to

give birth to twenty children and that throughout the

whole childbearing stage in her life she produced a child

year after year. Out of this total some five children sur

vived, quite a large number. If, therefore, a woman bur

ies her children each year her attitude towards death is

totally dissimilar to ours. She lives and simply gives birth

to successive offspring. The relation towards death and

life is totally different. In certain Latin American coun

tries I often accompanied groups of Indians. In Bolivia

or Peru, I would suddenly see a father carrying a small

coffin made of plain boards to be buried in a cemetery

high in the mountains. A thing quite inconceivable in

would not perceive anything blameworthy in those phe

nomena. Naturally, this is connected with the fact that

we are living in a world of intensively functioning mass

culture and, as result, a world of enormous deposits of

kitsch, which has already become a permanent element

of culture. Some might find this to their liking, while

others might not; these mass culture phenomena can

be ignored or criticized but they shall objectively exist.

Willingly or not, we are compelled to participate in this

process.

Z. Benedyktowicz: My question about American

culture has also a second hidden agenda. Naturally, we

know enough about American pop culture and numer

ous phenomena, including embarrassing ones, from this

particular domain. On the other hand, if we inquire

about the best chairs of classical philology in the world

then it turns out that, as Zygmunt Kubiak said during

a discussion held by our editorial board, ancient Greek

studies flourish best at Harvard...

R. Kapuściński: It must be kept in mind that Amer

ican society is highly diversified. The campus phenom

enon takes place also in this world. But this is a closed

enclave, almost totally isolated from society. It is, and is

not, America. True, in each academic domain you en

counter all: means, ambition and talent. These people

are intentionally drawn there and enjoy excellently or

ganized work. Such campuses represent the highest pos

sible level. The whole problem consists of the fact that

they exert but a slight impact on the rest of the country.

This is also the reason why I find it difficult to say that all

those phenomena are actually “America”, just as those

who are familiar with Africa find it difficult to use the

name: "Africa”. “America” and "Africa” are comprised

of so many realities simultaneously, so many different

worlds, at time highly contradictory, that the applica

tion of a single name in order to encompass everything

is simply misleading.

z . Benedyktowicz: I would like to ask about yet an

other detail, closely connected with historical trauma

and ways of overcoming this sort of memory. In his re

view of Rondo de Gaulle’a, a book by Olga Stanisławska,

Jacek Olędzki wrote about an issue strange for the Euro

pean: African museums, even those focused on coloni

alism, lack martyrological memory. In other words, the

strong presence of the cult of ancestors seems to have

replaced remembrance, that specific process of concen

trating on the painful past so familiar to us from personal

experience. Is this really the case?

R. Kapuściński: Let us start from the fact that there

are no European-style museums in Africa. They are mu

seums only because that is their name and they do not

display anything of special importance. No such institu

tions exist. Local culture and tradition lack a remem

brance site of the “here men were shot, there they were

32

�Ryszard Kapuściński • ON MEMORY AND ITS THREATS - RYSZARD KAPUŚCIŃSKI

Poland, but understandable within the rules of local cub

ture.

why he travelled across the world, attempting to render

the Greeks aware of the nature of their culture when

facing other cultures.

Z. Benedyktowicz: Thanking you for accepting the

invitation of our editorial board and for the stimulating

conversation I ask once again: when can we expect your

book to be published?

R. Kapuściński: Without disclosing too much I

would like to add that this book has produced grave

problems. I chiefly have in mind the way in which I

should control the entire classical material. After all,

there recently took place a significant breakthrough in

historical research, and in the past years we have all wit

nessed a great revolution in this domain. Consequently,

unruffled traditional science about antiquity is starting

to become somewhat part of the past. There exists a

vast new literature on the topic, with which I am mak

ing my very first acquaintance. Since the whole time I

have maintained contacts with my friends, experts on

antiquity, they assist me by proposing various interesting

titles and urge: “Look, this could be useful, and you must

read this or that”, to which I respond: ”1 shall never fin

ish writing this book!”. Naturally, the proposed studies

are extremely interesting and I eagerly study them since

they recommend is an entirely new approach to history,

extremely vital and in accord with novel tendencies de

scribed as postmodern. Consequently, there is no way

out: this Herodotus is still growing.

Arrangement of discussion

Dariusz Czaja

The editors would like to thank

the author and Ms. Iza Wojciechowska

for the photographs and cooperation.

“I shall never finish this book!”

Z. Benedyktowicz: I have the impression that so far

we have said too little about the book you are now writ

ing: Podróże z Herodotem. Here are a few details. I know

that the book, albeit with a famous ancient historian

in the background, originates from individual, private

memory...

R. Kapuściński: ... both mine and his. To a certain

extent this is a highly autobiographical book based on

authentic experiences. Everything started when in 1956

I was presented with the idea - an exercise of sorts - of a

voyage to India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Naturally, it

accompanied me all over the world although not always.

Now, years later, I read Herodotus anew. But this is ex

actly what happens with a book - obviously, if it is good

and outstanding. It turns out that each time we read

it as if it was new. The extraordinary feature of a great

book is the fact that it contains many books, or rather

their endless number. One could describe it as multi

text. The extraction of those assorted texts depends on

when we read the book, in what sort of circumstances,

mood, and situation, and what we seek in it at the given

moment.

Summing up: I regard Herodotus to be a teacher of

sorts, who taught me perception of the world as well as

an attitude towards others and different cultures. After

all, he was the first globalist, the first to understand that

in order to comprehend one’s culture it is necessary to

become acquainted with others, since the essence of our

culture is reflected only in the latter. This is the reason

33

�